Death is something that children don’t understand. I’m not sure that the adult mind can understand it, either. The loss of a human being is irrevocable, and our minds don’t see it as logical or acceptable.

Death is something that children don’t understand. I’m not sure that the adult mind can understand it, either. The loss of a human being is irrevocable, and our minds don’t see it as logical or acceptable.

When children encounter the death of a classmate, a friend or family member, it can really shake a child’s world.

Suddenly, life doesn’t feel as safe. Suddenly, the adults around the child are struggling with simple daily tasks. Suddenly, it’s difficult to play, or difficult to find someone to play with. There’s no way around the big punch a death makes in a child’s sense of safety.

But there are many ways to support children through this experience, so that it hijacks the smallest possible amount of their confidence, and so that they can recover fully, with a better understanding of the world and of the power of their parents to care, to build community, and to make a good life, even under adverse circumstances.

When a death occurs, get listening time for yourself.

One of the hardest things about a death for children is how emotions take over the lives of the grownups around them, and how those emotional clouds can move in and remain for months or years, because the grownups don't get the help they need to express their feelings. Working through grief isn’t just about missing the person who’s been lost. It’s about repairing the break a death creates in our sense of safety, our sense of the goodness of life, and in our sense of having the support and the hope we need to be fully ourselves, able to live each day well.

So the first thing that will help a child is for you, the parent, to work on whatever feelings you have about the death that has occurred. Don’t worry about whether the feelings you have are “typical” feelings or not. The way we feel about a death can go from celebration (which is how a partner may feel when a rancorous or deeply dependent person dies) to deep grief, from anger and insult to feeling helpless and alone.

Your spontaneous reaction is the feeling to talk about in listening time, and to allow yourself to release in laughter, crying, or trembling. Focus on the first feelings that come up, followed by others, and then still more. Stay aware of how your feelings shift, and keep unloading them with a listener (not with a child, of course—but you know that!). If it’s a person in your direct family who has died, you’ll probably need to keep paying attention to your feelings about the death for months, and for years. It’s worth paying attention here. You’ll be clearing out long-held places of worry, self-doubt, and upset as you go.

So call a friend, call a good listener, and ask them to do you the favor of listening, without interjecting their thoughts or their stories. Tell them everything that's on your mind. That will be a good start.

When you are able to notice and offload your feelings, your goal is to be as fresh and present to your child as possible. Your child will have her own very individual reaction and response to the death that has occurred. You’ll be a good listener and a good support to her if you continue finding adult support for the feelings that come up for you. You are aiming to be able to have moments of peace, moments of play, moments of awareness of the goodness of life, right next to your awareness of the deep loss of an irreplaceable person.

Band together as fully as you can

I think the main thing that helps children deal with a death is dealing with it together, together, together. Asking for and building a team of mutual support is vital.

Figure out how to tell the children together. Figure out how to honor the person who has died together. Figure out how to play and have fun in that person’s honor together. Figure out how to talk about that person frequently, together. Figure out how to support one another, so that people who need time and support to grieve fully, get that time and support. Figure out how the children can still have times when they can play fully, with no attention on their loss. Figure out how to ask for help, not just in the immediate weeks, but also over time, so that the emotional fallout can be dealt with thoroughly, and all can recover well.

Establish distinct times for working through feelings

It’s useful to remember that we are much healthier when we don’t sit around, stewing in feelings that are expressed only in body language. So for someone who has slumped into sadness but is not crying, a good walk around the block with a friend, or going to the park to see children playing can get the tears going, but sitting in a dark room alone doesn't. It’s good to offer dedicated listening time so grief can come out, and then to help the person clear their attention for daily tasks, coming back in a few hours to listen again to their grief, but helping them put their attention on the reassurance of daily life in the meantime.

Explain the adults’ unavailability to children

If one person in the family or the community is deeply affected by the death, explain this to the children, and help them understand what to expect. For instance, “Daddy is sad, and he’s tired from all the things he needed to do when grandma died. That's why he's not so playful right now. But he said he would do Special Time after dinner for ten minutes, so you can look forward to that.”

If one person in the family or the community is deeply affected by the death, explain this to the children, and help them understand what to expect. For instance, “Daddy is sad, and he’s tired from all the things he needed to do when grandma died. That's why he's not so playful right now. But he said he would do Special Time after dinner for ten minutes, so you can look forward to that.”

Think about your beliefs, and how you want to communicate them

When explaining death, don't pin it on, “He was old,” because that can set in a fear of old people, and of aging. Most people die because of illness or wear and tear or accidents. Tell the truth, very simply. Then answer your children's questions, as simply as you can. You can draw analogies to nature’s cycles, you can talk about life replenishing itself, you can add the perspective from your religious background, or you can let them know that, “Some people think that a person’s essence lives on, and it certainly does, inside all of us, because we knew so-and-so well, and we won't ever forget her.” Here’s where you get to pass on the unique beliefs and insights that are a treasure for your child. If you don’t know what to say, use your Listening Partnership to figure out first, what you don’t want to communicate. The perspective you do want to offer to your child will come clearer when you’ve done that.

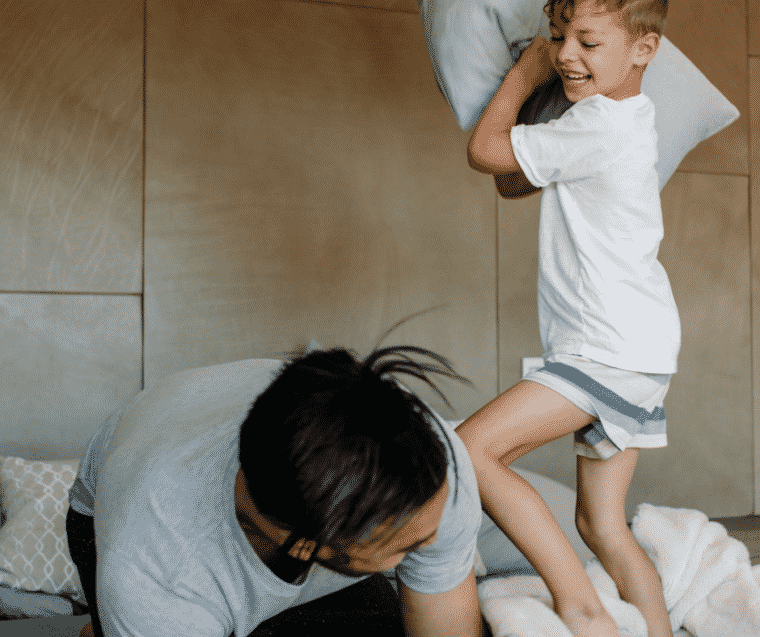

Playtime is vital, even when children are grieving

Children need to play every day, even if they've just lost someone very important to them. So do what you can to make sure that play is OK, and encouraged. When it's someone very close, a good playtime with lots of laughter will allow for more emotional release of grief later. If the adults around a child who’s had a death in the family are thunderstruck, it’s time for other friends and allies to come in and set up playtimes.

Children will release their deep feelings by wrapping them around small issues

Children usually bring up their deep feelings of loss and other feelings around the death of someone they love via the small imperfections in daily life. The egg on their plate at breakfast is too cold; they don't want to put on their jacket to go out in the snow; they insist on changing their socks until the socks feel “right,” and no pair of socks feels “right.” Get close, then gently, warmly set a reasonable limit, and let the emotional episode begin. It will lead to your child’s reservoir of grief and fear if you listen with warmth, and say that you care, but not more. The child will stay focused on what's “wrong” in the present moment, but his or her feelings will escalate into wild and frantic territory the longer you listen.

You don't need to (and shouldn't) say a thing about “Is this about So-and-So dying?” Just keep gently pointing to the issue that set the child off. “Sweetie, you've tried enough socks. Are you ready to put your shoes on now?” and variations on that theme can be good for a whole hour of emotion. Don’t psychologize. Just care, and let your child have the relief she’s eager for.

Allow children times and ways to express their thoughts and caring

Give children a chance to express their thoughts and love. Making drawings, composing songs, sending a letter to the person who died or to their kin, offering a gift or flowers—let your child decide what he or she wants to do, and support the expression of their caring. It’s very difficult on children when there’s no positive way for them to show their thoughts or love. Create this opportunity, assist them with it, and create it again in a few days, weeks or months.

When repetitive questions persist, gently move your child toward connection through play

Sometimes, a child wants to ask about the death again and again. You give the information or perspective you think will help, but after the tenth question, you can tell that his fears are preventing your information from satisfying his mind. He can't absorb what you say: his feelings stand in the way.

We recommend, at this point, trying a gentle Playlistening intervention. After the 10th time of, “Where is So-and-So now?” or “Am I going to die? When am I going to die?” give her once again your most loving perspective. This might be something like, “Honey, you're alive and well, and I'm protecting you every single day and night. You're not going to die any time soon. I don’t intend to die any time soon. We can go ahead and enjoy having a good life together.” Then, try a version of the Vigorous Snuggle. You might scoop her up, and merrily carry her around the room, saying, “We're A-LIVE! We're A-LIVE! We're A-LIVE and here to play! Here to play! Here to bounce and sing and PLAY! And with that last word, snuggle her vigorously.

Or offer her a pillow and wiggle your backside invitingly. Or plop her on the bed, and plop on the bed beside her, hoping to get a little physical play going. Look for a little laughter. Try to spark a break in the worry-clouds. Laughter will get your message, “Everything is OK,” through better than any rational explanation. They need to hear your rational explanations occasionally, yes. But when you can tell there’s a broken record playing, try play!

Or offer her a pillow and wiggle your backside invitingly. Or plop her on the bed, and plop on the bed beside her, hoping to get a little physical play going. Look for a little laughter. Try to spark a break in the worry-clouds. Laughter will get your message, “Everything is OK,” through better than any rational explanation. They need to hear your rational explanations occasionally, yes. But when you can tell there’s a broken record playing, try play!

Perspectives that might benefit your child

To figure out what perspectives might help your child, think about what you would have liked to hear from a warm adult when you were young. What did you worry about? What scary scenarios did you picture? What would have helped?

Here are a few very general things I think might helpful, but whatever you come up with will be good here. Your child needs your perspective, this is just to get your thinking going!

So, just to start things off, here’s my list:

You are healthy, they are healthy, and you expect to be together with them for SO many years.

That you are doing everything you can to be sure that you can be their mommy, and they can be your son/daughter, for so many years it's hard to count them all.

When someone dies, the thing we do is to get together and help each other with everything. The goodness of that person never ends–it gets passed on, through the people that knew him, to others every day.

That we still have the power to love that person, and never stop, even if they can't be with us any longer. The fact that they died doesn't have to end our powerful love.

That the grownups are going to be feeling more feelings for a while–that's what needs to happen when someone dies. But it won't last forever. Daddy/Mommy (or the people they know most closely involved) will be playful again as soon as they can. And you, my child, don't have to stop playing. You don't have to feel the same way Daddy or Mommy (or other people) feel. Everyone is different. We’ll play when we can play, and cry when we miss that person. And both of these things will honor them.

We will never forget So-and-So. So-and-So is precious. And if you feel like So-and-So is being forgotten, please let me know, and we’ll remember him/her together.

Should children be invited to a funeral or a wake? Should they see the body of the person who has died?

I think that this issue is best handled individually, family by family. Moving far beyond your own comfort zone to do what a parenting author advises is probably not going to be helpful to your child. However, I think that, in general, shielding children from a death isn’t helpful to them. Personally, I will be forever grateful to my parents for sneaking me in, against hospital rules, to see my very ill sister before she died, although she couldn’t recognize my parents or me. And I was so glad to be at her funeral.

I think children can be trusted to handle seeing a dead body. What anchors them is a thoughtful adult nearby, who has the ability to offer caring and attention while this very important experience is happening. What’s harder for a child is being exposed to unremitting adult absorption in feelings of helplessness and hopelessness that sometimes accompany grief. A few explanations ahead of time will help orient the child.

For instance, “Auntie Agnes is probably going to be crying a lot, but don’t worry. We’ll be sure that someone who loves her is with her,” or “I’ll go with you if you want to see Uncle Elmer’s body. It might look kind of odd, because when people have died, they don’t look quite like themselves any longer. If you don’t want to, that’s OK, too. I’m going, because it will probably help me cry and say goodbye to him in my mind.”

With this kind of gentle guidance and attention, children can manage even very difficult situations. They will have lots of feelings to work through when the immediate situation goes back to its more normal shape.

Special Time, Playlistening, Setting Limits and Staylistening will all be useful in the ongoing project of helping them with the feelings that linger. Your ability to keep clear on your own feelings will help you stay fresh and available, so the healing progresses for you all.

For more on using play to help support children read Playlistening: Play that Lets Children Lead

Find out about the therapeutic and clinical benefits of Hand in Hand Parenting