Q. We were at a school picnic when some of the children began teasing my child. They called him a “baby!” and basically treated him like he wasn’t worthy of their attention. It was horrifying and really upset me. What should a parent do?

I’m sorry this happened to your child. It’s unfair, heartbreaking, and shocking for both parent and child. And yet it’s a common occurrence in groups of children, one that happens so often in part because adults don’t know how to respond effectively to the underlying issues that drive this kind of behavior.

I’m sorry this happened to your child. It’s unfair, heartbreaking, and shocking for both parent and child. And yet it’s a common occurrence in groups of children, one that happens so often in part because adults don’t know how to respond effectively to the underlying issues that drive this kind of behavior.

How teasing behavior gets started

Children only act harshly toward other children when they are overtaken by emotional tension. When children feel connected and secure, and are being treated with respect and warmth, they feel safe, feel seen, and can think, learn and act generously toward other children. The child who teased yours was clearly not feeling safe or secure at this function, or he would not have acted in that way. He may have looked like he was perfectly fine, but even children have to learn to cover their upsets, because parents are often too stressed to welcome children’s display of feelings.

Children who are targeted by tense or harsh interactions internalize that treatment. It is recorded in their mind in a very literal way. Any (and every) harsh word, stereotype, put-down, or brush-off (“Oh, would you just stop whining! You sound like a baby!”) in a moment of parental stress sticks in a child's mind. The interaction literally doesn't compute. The child feels hurt, feels the emotional charge behind the words, sees the body language of the parent or sibling or neighbor, and all this information gloms together in the child's mind, along with every detail of the attitude that he witnessed.

When children feel upset by an experience, they tend to act that experience out with others. The larger the group, the more the child's limbic system, the social-emotional center of his mind, seems to signal, “Someone here will probably be able to help you with this disturbing incident you experienced. Why not see if you can get some help with it?” Out comes the harsh, hurtful behavior, a little piece of recorded history being replayed, with the child as the aggressor this time. The child isn't thinking. He’s rehearsing something that he saw acted out at him, or at someone else. And he’ll keep on teasing until this undigested experience can be resolved.

A child’s attempts to get help with teasing behavior backfire

A child who teases has been teased or put down, or has witnessed other children being teased or put down. He has been frightened by the experience. He's looking for help in the only way he knows how, but his efforts backfire most of the time, because all the adults around him react in negative ways.

Adults have been teased and taunted earlier in their lives, and their responses are shaped by the adult anger they witnessed when this kind of incident happened long ago. An adult will freeze, just like she did when she was targeted as a child. Or if an adult was harshly punished for teasing and taunting, she reacts with harsh punishment. Or she hated that harsh punishment, and has consciously decided never to act it out, she’ll freeze, not knowing how to respond without attacking the teaser. Some adults, who were feisty as children, will pick a fight with the offending child or the child's parents.

In any case, the adult is driven by what she has seen or heard in the past, and that past has not usually included empathy for the teaser! Adults are not often aware that they are reacting. Often, they feel that their actions are logical and sensible, given the teaser’s behavior. It’s not easy to remember that the teaser is caught, too, and needs help out of this hurtful behavior.

One typical adult response is to try to defend the child who has been targeted, by targeting the teaser. That child is scolded, punished, lectured, or forced to make a false apology. All this becomes another hurtful and indigestible interaction that does the offending child no good at all. The adult’s anger and punishment translate into another threatening experience. Nothing is learned because the child's mind cannot function during moments when his inner guidance system detects threat or harm. He gets through the experience, one way or another, but his tendency to tease will pop up again, with added emotional tension behind it, because that behavior still needs some kind of resolution in his mind.

Another response, also problematic, is that adults, trying hard to be civil, just let it go. The behavior goes seen, heard, disliked, but unmet with any limit or intervention. In a way, this response is a step in a positive direction, a step away from attacking a child who just needs some help.

It may be better than hurting one child for hurting another, but it is no solution. The child who is teased is not protected, the teaser gets no help, and the children witnessing the incident see everyone freeze in place. Trying to ignore the teasing is a sure guarantee that the “behavior infection”—those words, those tones, and that stinging emotional barb, will infect all the children who were nearby. Now they, too, will tend to tease like that, trying to get some kind of help with the behavior they witnessed. This is how schoolyards become such difficult places. One “infected” child plays out the problematic behavior, and everyone witnesses it, and then feels compelled, sooner or later, to act it out.

Adults who want to help a teaser need a bit of assistance themselves.

What are some helpful responses to a teasing child? We parents need to face the fact that you can't help children when you're upset at them. A parent can manage some semblance of a non-hurtful intervention, but if her heart isn't in it, the intervention, though decent at the moment, won't move things forward for the teaser.

It makes a big difference if you find a listener, and work on your upset about teasing. Show it. Say what you feel like saying to any child who behaves that way. With a listener, be snippy, be cutting, let the reactions you manage show! The closer you get to the hot, roaring truth of your emotions, the better the chance you have of choosing your response next time. You'll have plenty of chances to intervene–children are not going to stop teasing or taunting one another any time soon!

So talk about incidents you remember in your childhood, about siblings and how they treated you, about adults meting out punishment in your family, about things they said to you. It all relates to you regaining your ability to think when a child throws out a taunt. You want your mind “on,” and your perspective still standing. You want to be able to have the thought, “Here is a child who needs some help. He's caught in a behavior that's not good for him or for anyone. I'll see if I can help.”

Try humor and affection as you set a limit

What needs to happen is that a thinking, caring adult needs to intervene so that the child who taunts is not shamed or blamed, but is prevented from doing further harm to other children. You want to stop the behavior, but remain warm toward the child who is caught in it.

One of the best ways to do this is to come up with a vigorous snuggle response. Here's an article that describes this in fuller detail.

That would be something like, “Oh, when I hear that word ‘Baby', I just want to hug the person who said it! Anybody who says ‘Baby' gets a great big hug from me!” And then, grinning, you open your arms and start lumbering around, heading slowly but happily toward the child who was taunting. That will surprise the heck out of everyone, and it will change the whole situation. That child might start spouting, “Baby! Baby!” just to see what you're going to do, but the sting will be gone.

It will now be a game between you and him or her, a game in which you are offering goofy affection, meeting the child stuck in off-track-behavior-land with an intervention that's interesting, inviting, elicits laughter, and releases tension from the whole situation. Other children, just as eager to work on their name-calling tensions, may also begin chanting “Baby!” but no child will be the target. Saying “Baby” will become a bid for attention, a bid for laughter, a bid for affection, a bid for tension release and a way out of a moment that didn't feel good to anyone.

This is hard to do! But let me tell you that, after you've used a listener to vent your anger, your heated words and long-held desires to retaliate, it is a really powerful thing to see a hurtful situation disarmed in this way. You create laughter, which helps children feel enough connection to relax, while you meet the need of the teaser to be stopped and prevented from doing further harm.

When you can't pull this off, another intervention that is possible is to just go to the taunting child and try to turn yourself into the target. Go over, get down into a small position, and playfully do “baby” things. “Goo, goo! Ga, ga! Do you like me!?” A child's attack will be deflected toward you. If he persists, just tap him on the shoulder and say, “Hey, Jasper! Can't you tell? I'm the baby around here! It's me! I want to be the baby!” In my experience, that doesn't work as well as proposing playful affection, but it's another way of diffusing the tension, interesting the teaser, and changing the whole tone of the play group.

Try “Time In” with a determined teaser

And then, there's the more typical adult strategy. You can move in and just remove the child who is caught in stuck behavior. This can go well when the adult intervenes with little emotional charge, in the spirit of, “I'm going to help you stop. I know you don't want to be doing this.”

So you move in, say, “Jasper, I can't let you do that, let's take a little time together,” and pick Jasper up, or take his hand and bring him to another place. Sit with him, preferably close, arm around him. The only thing that's going to restore his ability to play cooperatively and positively is feeling some kind of connection, safety, and warmth coming from someone. You are it. Spend five minutes of “Time In” with the teaser, and then ask him, “What do you want to go do now?” and stay close while he gets back into play. If emotions are running close beneath the surface, your intervention will allow Jasper to cry, or to have a tantrum. If you can, listen to him, stay with him, and pay good attention while he expresses passionate feelings, the feelings that were hidden underneath all the taunting behavior.

Laughter, tantrums and tears help dissolve the roots of teasing behavior

Children don't hurt unless they don't feel good. They don't feel good because they have too much emotional hurt stored, and it's become unmanageable. Crying and tantrums let the hurt out, when the child is listened to by an adult who respects them and holds a sensible (but kindly offered) limit. Laughter, tantrums and tears actually reduce a child's tendency to target others, because he's got less emotional baggage to carry. Lectures don't work. They are always given while a child is feeling bad, and is therefore unable to think straight. The child endures the bad situation, but his mind is jammed. He can't learn a thing from the verbal “wisdom” the lecturer is trying to impart.

Connection works better. Offer connection, then quick intervention when the hurtful behavior erupts again, so that the feelings underneath have some chance to be expressed. “That's not fair! Why are you keeping me from playing? They get to play! Why do you always do this to me? I didn't do anything!” is a typical beginning of a good cry that gets to the root of a child's prickliness on the playground. Stick with your limits, don't talk, don't reason, just say, “Sorry, Jasper, we do need to take these few minutes. I can't let you call names.” and listen, listen, listen. Big feelings will come to the fore, and if an adult can stay and connect, good things will happen when the emotional storm has passed.

Here’s how it can work

One mom in a Hand in Hand class told us that she has contact with a child who shouts out insults at other children frequently. This child has the adults around him buffaloed. They either try to stay calm but allow him to remain obnoxious, or they remove their children from play with him. His behavior has been getting more pronounced over time, and this child is being marginalized because no one knows what to do.

She decided to try the idea of playfully drawing the child’s insults to herself the next time she saw him. It took only a few days before she had her opportunity. She and her daughter were at an ice cream shop in town when he and some other children arrived with their parents. Right away he began telling her daughter, “You stink!” The mom jumped in and said, “Oh, my, you’re mistaken! I stink! I just finished my workout! Here, smell me!” He laughed, and the other children laughed, too. She said he looked astonished, but pleased. He tried calling her ‘stinky ‘a few more times, and she responded with playful warmth, “Oh, I’m going to have to give anybody who calls me ‘stinky’ a great big raspberry!” The laughter rolled.

Her response delighted all of the children. She could see that her daughter felt empowered—she was no longer the target, and the person who was the target, her mom, was a happy, energetic one. After some moments, the mom told us, the heavy tone that had settled on the children was gone, and the name-calling was over, too. The mom knows that this child has a hard life at home. She told us that she felt quite powerful that afternoon. She offered some play, a generous heart, and a path away from hurtful behavior, without shaming anyone in the process.

From the Hand in Hand Toolbox:

- Read 20 Playful Ways To Heal Aggression to help banish bad feelings

- Are you watching your kids and their friends move offtrack? Try some silliness

- Tantrums when play comes to an end? Read Ending a Playdate with Connection

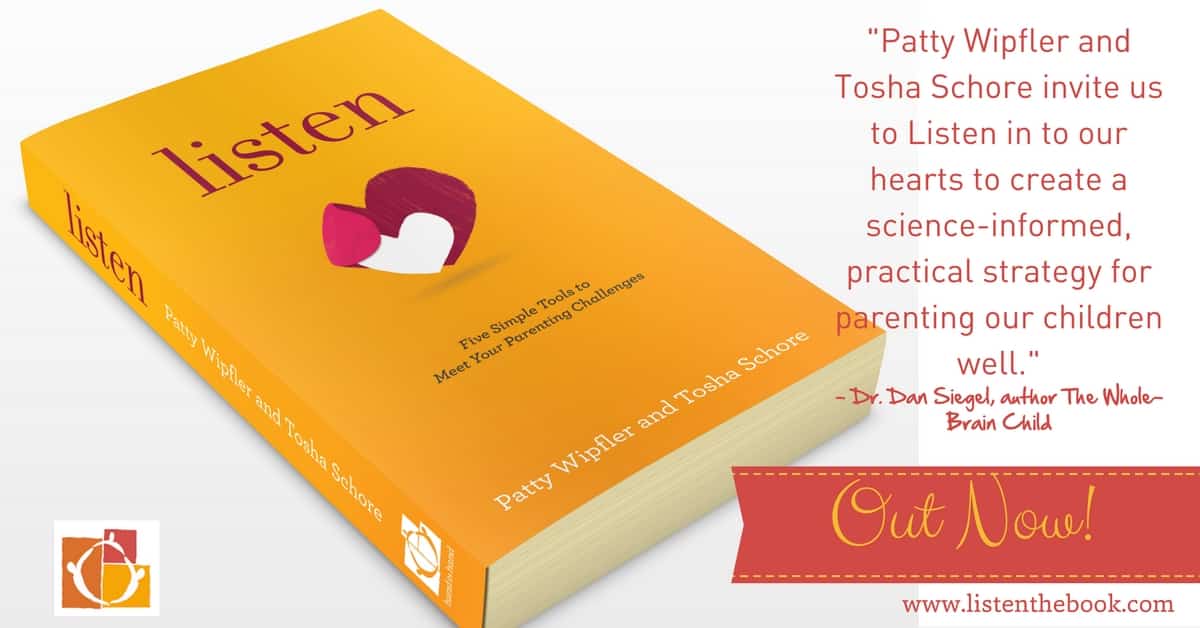

Our book is out now! Read a chapter and buy it here